“I don’t think social media had a great effect; it is overrated as a tool but I know others would disagree with me.”

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

Social media is popular as a cheap and easy way to broadcast campaign messaging. Increasingly, the public turns to social media as a ‘source of truth’ for news and information about politics.

Policing social media is problematic as the technology companies that run the platforms are based overseas and, until recent times, not subject to many Australian laws on content or publication of material. They have, so far, successfully argued that they are not publishers and therefore are not subject to defamation laws.

With the closure of local newspapers, Facebook was more important than ever in the 2020 council elections. Candidates were able to run a free campaign by setting up campaign pages and using existing community forums or they could pay for advertising.

The Australian Local Government Women’s Association (ALGWA) reported that in the campaign, social media advertising ranged from $50 to $7,000.14 Candidates who were more technologically savvy and had bigger advertising budgets had an advantage in targeting voters in their municipality.

“I found Facebook to be mixed. At times, trolls would jump on anything I posted immediately, and I know that there were former councillors who were encouraging the trolls. But at other times I found that if I paid for advertising, then I was able to get my message out and it was a really useful tool.”

– Councillor elected for the first time in 2020

“I was very low key during the election. I didn’t campaign and didn’t do a letterbox drop. The only thing I did was set up a Facebook page and ran a dog as a ‘candidate’. Using humour on social media helped.

– Councillor re-elected in 2020

However, social media creates audience silos where voters may only engage with things they endorse, and the social media algorithms confirm these biases. The result is that the electorate had limited exposure to alternative messaging. It also means politicians can avoid being challenged in a genuine debate.

We observed this behaviour in the 2020 elections with complaints about candidates blocking their opposition or deleting critical comments to curate their pages and present themselves in a better light.

Social media has proven difficult to regulate and moderate. It can also allow misinformation and disinformation to spread. This can be in the form of an individual posting wrong information or a coordinated political campaign. In addition, the truth can be manipulated by people who are able to remain anonymous.

During the 2020 council elections, ALGWA reported that there was evidence of ‘brigading’, where a group of people with dubious or fake profiles attacked candidates with negative, often intimidating comments in unison or as a group.

Another feature of the 2020 council elections was the use of ‘community pages’ or ‘community groups’ which post information about local issues and have community members acting as volunteer ‘administrators’ or ‘moderators’. These community groups on Facebook have hundreds or thousands of members and it is up to the administrator to remove comments or ban people who do not abide by the rules of the group. These groups do not have any oversight in the same way as traditional publishers, such as newspapers. ALGWA reported that during the 2020 elections, some administrators did not comply with their own group rules and shut down debate which they did not agree with. ALGWA also observed that a candidate that was an administrator for a group with thousands of members transferred the administration of the group to a family member during the election period and did not disclose a conflict of interest. ALGWA said critics have no ability to address or refute misinformation in these groups and voters can be easily misinformed.

In 2020, we received 351 allegations relating to online content, with 75 per cent of these allegations relating to social media, 10 per cent about email, 11 per cent about websites and 4 per cent not specified.

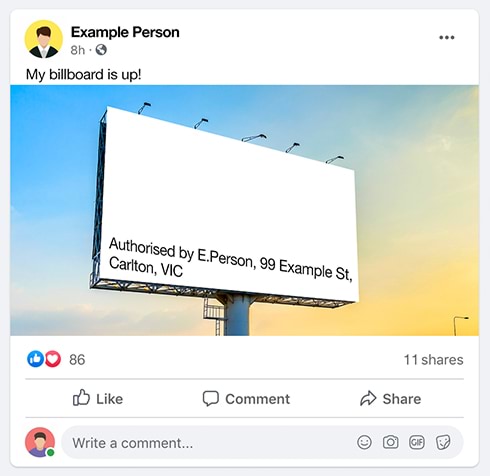

On 9 October 2020, we published a guide, with input from the VEC, detailing the appropriate method of ensuring social media posts are transparent and their author is clearly stated.

“It was virulent. Some of the stuff was atrocious. The problem is that Facebook is utterly unanswerable. You can request material be removed but they don’t take things down and people believe it.”

– Former councillor who did not stand for re-election

“My main opponent blocked comments on Facebook and deleted [negative] comments to make his feed look better. How can you oppose that? I took a different approach. I responded or acknowledged 95 per cent comments I received.”

– Councillor elected for the first time in 2020

We received 266 complaints from across the state related to candidates, ratepayer groups or supporters using social media to post about elections. This compares to the election period in 2016 when 78 complaints were lodged. Most of the complaints have involved potential breaches by candidates of rules around correct authorisation of social media posts or accounts.

As the newsrooms for local newspapers have closed, Facebook community groups run by administrators have sprung up to fill the void. Many complaints were made by candidates or their supporters against community group Facebook pages.

Recently, similar issues have been raised at the federal level and the Australian Electoral Commission has investigated the issue of community and news groups, their lack of transparency and the potential for political figures to misinform the electorate.

We received 38 complaints about commentary included on a website (excluding social media) and 34 related to email content sent by a candidate or authorised person.

“Social media didn’t have an impact on the number of women being elected but it did have a health and wellbeing impact on those that were being attacked. If you have just come out of a brutal election campaign then it doesn’t set you up very well for your new role in council.

“The keyboard warriors had an enormous advantage in 2020. If they were established on social media, then they had a huge advantage over those who were not as good or experienced using social media.”

– Former councillor who did not stand for re-election in 2020

14. Australian Local Government Women’s Association (Victorian Branch) submission to the Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry into the Impact of Social Media on Elections and Election Administration, 9 November 2020.

Case study

Updated