- Date:

- 17 Nov 2021

The Local Government Inspectorate’s Annual Report 2020-21 provides information on our progress in strengthening the integrity, accountability and transparency of local government in Victoria.

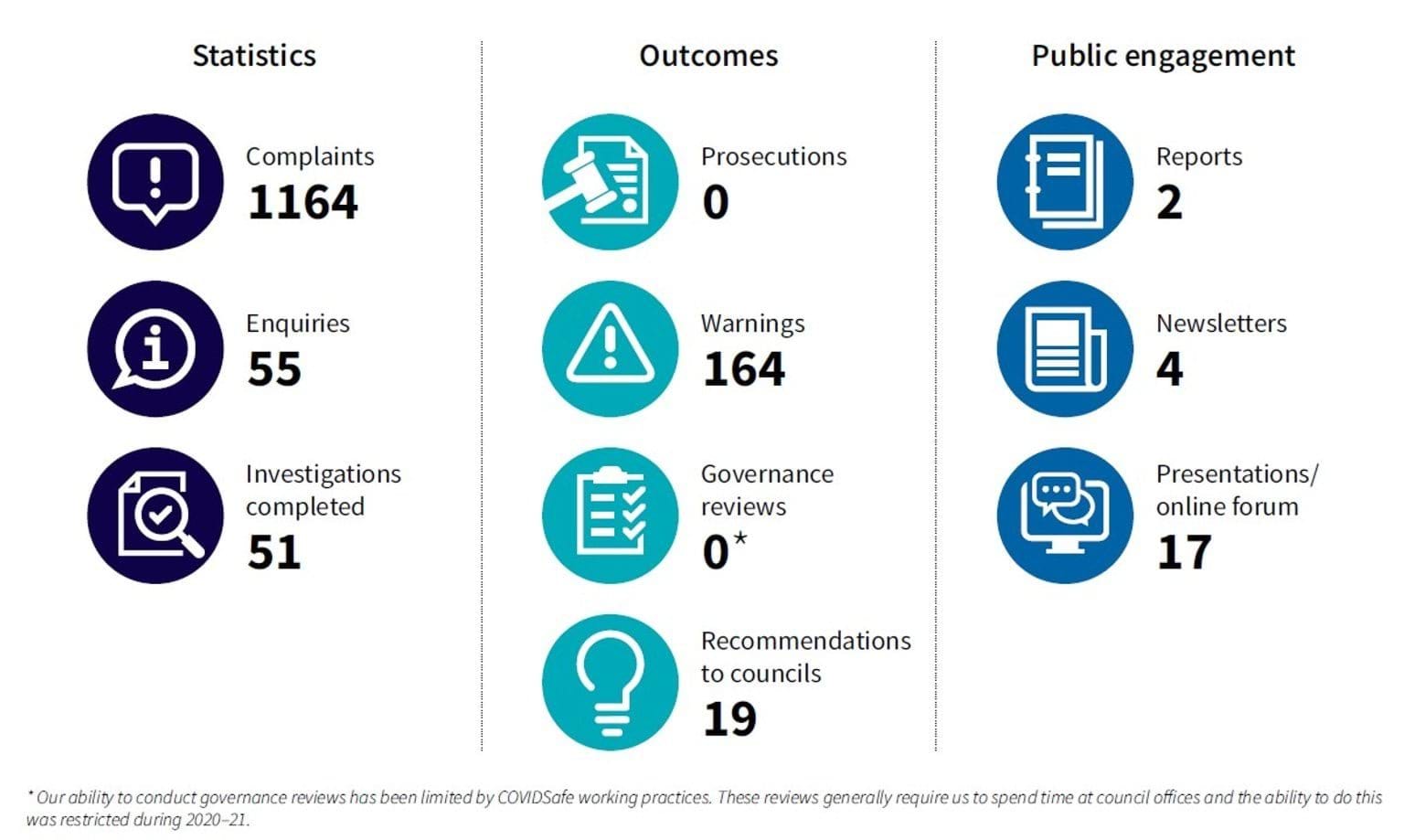

The Inspectorate received and assessed 1164 complaints and completed 51 investigations for the year. As with many public and private sector organisations, COVID-19 continued to challenge us; and our ability to interview and visit councils was affected. This report covers the 2020 general local council elections which take place once every four years.

Message from the Chief Municipal Inspector

I am proud to present the Local Government Inspectorate’s annual report for 2020–21, which is also my first report as Chief Municipal Inspector (CMI) after my appointment in April 2021.

COVID-19 continued to challenge Victorians – and councils – during 2020–21. We were challenged by multiple lockdowns, had to find ways of working safely and tried to support those who could not work.

Public health movement restrictions also provided additional challenges – and potential opportunities – for accountability and transparency. While councils had to limit public meetings and close down or restrict some services, this encouraged the growth of online meetings and forums and improved transparency of council activities to a wider audience. For the Inspectorate, the restrictions on movement forced the cancellation of planned face-to-face interviews and restricted our ability to visit councils and conduct legal proceedings. The COVID-19 restrictions also affected our education and prevention functions. I commend the professionalism and dedication of our staff in meeting these challenges.

In September 2020, we released a report on councillor expenses and allowances which made a number of recommendations to provide more guidance and consistency around the financial and other support given to councillors. We also recommended an increase in reporting and transparency.

The inspectorate prepared for months in the lead up to Victoria’s council elections, which were held in October 2020. The rise of the influence of social media and restrictions on movement as a result of COVID-19 led to a doubling of complaints to the Inspectorate. The election period saw our staff dealing with 36 complaints a day and we received a total of 848 complaints.

Administratively, we transferred from the Department of Premier and Cabinet to the Department of Justice and Community Safety as part of machinery of government changes in April 2020 and in December 2020, we transferred our systems. I would like to express my thanks to both departments for a smooth transition.

In May 2021, the third tranche of the new Local Government Act 2020 took effect. The new legislation is a major change for councils across the state and I commend councils for adjusting to the new rules and remind them that the adjustment period is now over.

We released a report on the 2020 general council elections in June 2021, which analysed the complaints we received and made 8 recommendations to help improve the integrity and democracy of local government elections. One concerning trend we looked at was the rise in complaints about social media and we recommended a change to the Act so that the rules and definitions of electoral material includes social media and online activities.

In October 2021, we published a report on personal interest returns following a major review of councillors’ personal interest returns. This review was undertaken during 2020–21 and covered 650 councillors.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge Dr John Lynch PSM, the Acting Chief Municipal Inspector from January 2020 until my appointment in April 2021. Dr Lynch led the Inspectorate through a difficult year and his knowledge, experience and dedication ensured we continued our vital contribution to the integrity of the local government sector.

Michael Stefanovic AM

2020-21 at a glance

Explanation of key categories and terms

Complaints: A complaint is a matter lodged with or referred to the Inspectorate for assessment in its capacity as the dedicated integrity agency for local government in Victoria. Most of the complaints we receive relate to councils but not all complaints we receive fall within our remit.

Enquiries: These include relevant contacts with the Inspectorate other than recorded formal complaints. Enquiries may involve multiple contacts with the public but only a single reference is included here.

Investigations completed: When the Inspectorate receives a complaint, an assessment is conducted to determine the best course of action. Formal investigations are resource-intensive, so we are only able to dedicate resources to a limited number of investigations at any given time. Considerations for allocating resources include the prospect of matters proceeding to prosecution or being the subject of a public report.

Prosecutions: The Chief Municipal Inspector is empowered by the Local Government Act to prosecute individuals in a court. This power is taken very seriously and prosecutions are only pursued under certain circumstances. The Inspectorate must consider whether there is a reasonable prospect of conviction, whether or not it is in the public interest and whether or not there is an alternative to prosecution that may be more appropriate.

Warnings: A warning is issued when a prima facie breach of the Act is substantiated, but circumstances show that a prosecution may not be warranted. Warnings given to a person are considered if any further substantiated complaints are made against the same person.

Complaint assessment: When the Inspectorate receives a complaint, it undergoes an initial assessment to determine, among other factors, if the allegations fit within its legislative remit or the matter should be transferred to another agency. A matter is not considered under investigation at this stage.

Prima facie: In the Inspectorate’s work, this refers to the presence of sufficient evidence to establish a fact or raise a presumption unless disproved or rebutted. It can also refer to matters that, on first appearance, may be a breach of offence under the Act but are subject to further evidence or information.

Public interest disclosure: In some circumstances, a complaint may be considered as a public interest disclosure (previously known as a protected disclosure or ‘whistleblower’ complaint). If a complaint appears to show that a councillor or member of council staff has engaged or proposes to engage in improper conduct, this could constitute a public interest disclosure. These matters must be sent to the Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission (IBAC) so they can determine whether or not the protections under the public interest disclosure regime apply.

What we do

What we do

The Local Government Inspectorate is a dedicated integrity agency for local government in Victoria and has the remit to investigate offences and breaches under the Local Government Act or examine any matter relating to a council or council operations.

The Inspectorate’s work can be categorised under 3 main themes – responding to community need (reactive), ensuring compliance (proactive), and our guidance and education function. Reactive work includes responding to requests for information and enquiries, assessing complaints, conducting investigations and in some cases, prosecutions. Proactive work includes specific council governance examinations and reviews of systemic or thematic issues across the sector. Our guidance and education to the sector is generated by our reactive and proactive work outcomes and includes newsletters, presentations, reports and other communication tools.

The Victorian public sector provides vital community services and facilities that support Victorians. Every day, public sector employees in government departments, agencies and local councils make decisions that affect all Victorians. The community expects people working in the public sector to perform their duties fairly and honestly. When misconduct or corrupt activities are not identified or left unchecked, public money and resources are wasted. Misconduct and corruption undermine trust in government and damage the reputation of the public sector.

The Victorian integrity system exists so Victorians can have confidence in the state’s public sector. Corruption in councils, government departments and agencies can negatively impact broader communities. Public sector corruption can occur when a public sector employee misuses their position or power for some form of gain. Some examples of public sector corruption include providing services to family and friends ahead of other members of the community, misusing information to help a particular company win a contract or accepting bribes or other benefits. Our integrity system also consists of integrity agencies such as IBAC, the Victorian Ombudsman and the Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Who are the Victorian integrity agencies, what do they do and what complaints can they deal with?

The Local Government Inspectorate

The Inspectorate investigates matters related to council operations including criminal offences involving councillors, senior council officers or any person subject to the conflict of interest provisions of the Local Government Act 2020.

The Victorian Ombudsman

The Ombudsman investigates the actions, decisions or conduct of public sector organisations and their staff. It also looks at whether a public sector organisation has acted in accordance with the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006.

Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC)

IBAC is responsible for exposing and preventing corrupt conduct in the public sector. It deals with serious corruption and misconduct in:

- state government departments and agencies

- Victoria Police

- members of parliament

- judges and magistrates

- council employees and councillors.

Highlights and challenges of 2020-21

New Chief Municipal Inspector

Michael Stefanovic AM started as Chief Municipal Inspector (CMI) in April 2021. Mr Stefanovic has 35 years of experience undertaking complex investigations in high-risk environments both within Australia and abroad. He was admitted as a Member of the Order of Australia for his significant service.

An expert in his field, having led teams specialising in fraud, corruption and misconduct investigations with the World Bank in Washington DC, he also served as the Director of the Investigations Division at the United Nations in New York.

Michael started his career in Victoria Police and served for 14 years in various roles, attaining the rank of sergeant. He has lectured at the NSW Police College and was Director of Investigations for the Royal Commission into the Management of Police Informants.

Michael is a sessional member of the Victorian Police Registration and Service Board. He holds an Associate Diploma in Police Studies, a Bachelor of Arts – Police Studies, a Graduate Diploma in Organisational Behaviour, a Master of Arts – Police Studies and a Master of Laws – International Criminal Law.

Ongoing impact of COVID-19 on operations

Travel restrictions due to COVID-19 impacted the ability for investigators to conduct in-person interviews, consequently extending the time frame for the completion of investigations. COVIDSafe working practices impacted on complex investigations at three regional councils and the planned reviews of Yarriambiack and West Wimmera councils’ compliance with findings from investigations in 2018– 19.

Our team faced challenges when transitioning to working from home but set up online working groups dedicated to election complaints. Inspectorate staff dealt with an average of 36 complaints a day during the council election period, double the number of complaints from the 2016 election period.

Complaint Management System (CMS)

The current Lotus Notes-based CMS has reached the end of its lifecycle and is no longer supported by the Victorian Government IT provider, CenITex. Producing investigation reports and statistical analysis using the

current CMS is labour intensive and replacing the system is an urgent priority.

Work has commenced replacing the CMS with a fit-for-purpose system. The Inspectorate is working closely with technical experts from the Department of Justice and Community Safety to identify alternative systems.

Parliamentary privilege

Unlike other Victorian integrity agencies, reports published by the Inspectorate are not tabled in Parliament and subject to parliamentary privilege. This can delay the publishing of investigation findings while the Inspectorate responds to information requests from stakeholders and seeks legal advice prior to publication.

A major investigation - completed by late 2020 - has required the engagement of legal counsel to assist with concerns over the publication of the investigation outcomes

New legislation

The Local Government Act 2020 provisions commenced in four separate tranches. The first two tranches came into effect on 6 April 2020 and 1 May 2020. The third tranche commenced on 24 October 2020 and included qualification of councillors, strategic planning and budget processes, gifts, conflict of interest, personal interests returns and improper conduct. The fourth and final tranche commenced on 1 July 2021.

Responding to community need

How the Local Government Inspectorate responded to community need during 2020-21.

Enquiries

The Inspectorate regularly receives enquiries from community members, councils and councillors seeking advice, information or raising issues that fall outside the Inspectorate’s jurisdiction. Other enquiries received by the Inspectorate are often referred from other state government agencies and sector representative bodies. The Inspectorate endeavours to assist with enquiries where possible.

Complaints

The Inspectorate receives allegations pertaining to offences and/or breaches under the Act and has a responsibility to assess all complaints as part of its role. Investigators initially assess whether the allegation is within the Inspectorate’s jurisdiction. Complaints are then subject to an ‘initial action’, where evidence is gathered to determine whether the allegation can be substantiated. This process will determine whether the allegation constitutes a breach or offence under the Act, if it should be referred to another responsible authority or if there is no breach or offence under the Act.

There were 1,164 complaints accepted for assessment by the Inspectorate in the 2020–21 financial year. This almost tripled the previous year’s complaint volume and is in line with the overall trend of an approximate 11% increase in complaints across the four-year council cycle.

Investigations

While complaints are a main driver of investigations, the Inspectorate may launch its own motion investigation into any matter that potentially breaches the Act. During 2020–21, 51 investigations were completed.

| Reporting period | Complaints | Investigations complete |

|---|---|---|

| 2016-17 (election year) | 576 | 56 |

| 2017-18 | 417 | 39 |

| 2018-19 | 421 | 29 |

| 2019-20 | 336 | 22 |

| 2020-21 (election year) | 1,164 | 51 |

As with the previous financial year, major investigations drew significant resources, and a reduction in staff resulted in a decreased capacity to investigate. These challenges have been offset by an improved initial assessment process, which has enabled complaints to be assessed and either dismissed, referred to other agencies or allocated to an investigator in a more efficient manner.

Coercive powers

Under the Act, the CMI has powers to require the provision of reasonable assistance, which may require the production of documents and evidence or require a person to appear for examination under oath. In 2020–21, the use of the powers were approved on 50 occasions to obtain documents or interview people.

We interviewed 28 individuals in 2020–21 and the vast majority of interviews were voluntary. We used our coercive powers once to interview one individual.

Warnings

Warnings are issued for matters where a breach of the Act is substantiated but an alternative to a prosecution is considered to better serve the public interest. During 2020–21, we issued 139 warnings in relation to the council elections, 22 in relation to interest returns and a further three warnings. Warnings are used as an educational tool in making recipients aware of their obligations under the Act and of the consequences for further transgressions.

Compliance actions

Compliance actions in 2020-21 by the Local Government Inspectorate.

The Inspectorate conducts both council-specific governance examinations and broad reviews of systemic or thematic issues identified during council visits, investigations or feedback from the sector or the general community.

Examinations and audits of council governance arrangements are a key proactive function of the Inspectorate in assessing the effectiveness of councils’ risk management and governance processes. The objective of this function is to ensure council operating procedures are compliant with relevant legislation and avoid breaches of the Act.

The Inspectorate has a proactive function to encourage better governance in councils, and a reactive role in reviewing governance procedures.

During investigations into Wyndham City Council in 2016–17, the Inspectorate detected many issues with councillors’ interest returns, and subsequently undertook a comprehensive review of councillors’ personal interest returns across Victoria to determine the overall level of compliance. The review also allowed the Inspectorate to provide more informed input into the Local Government Act 2020.

Guidance and education

The guidance and education work done by the Local Government Inspectorate in 2020-21.

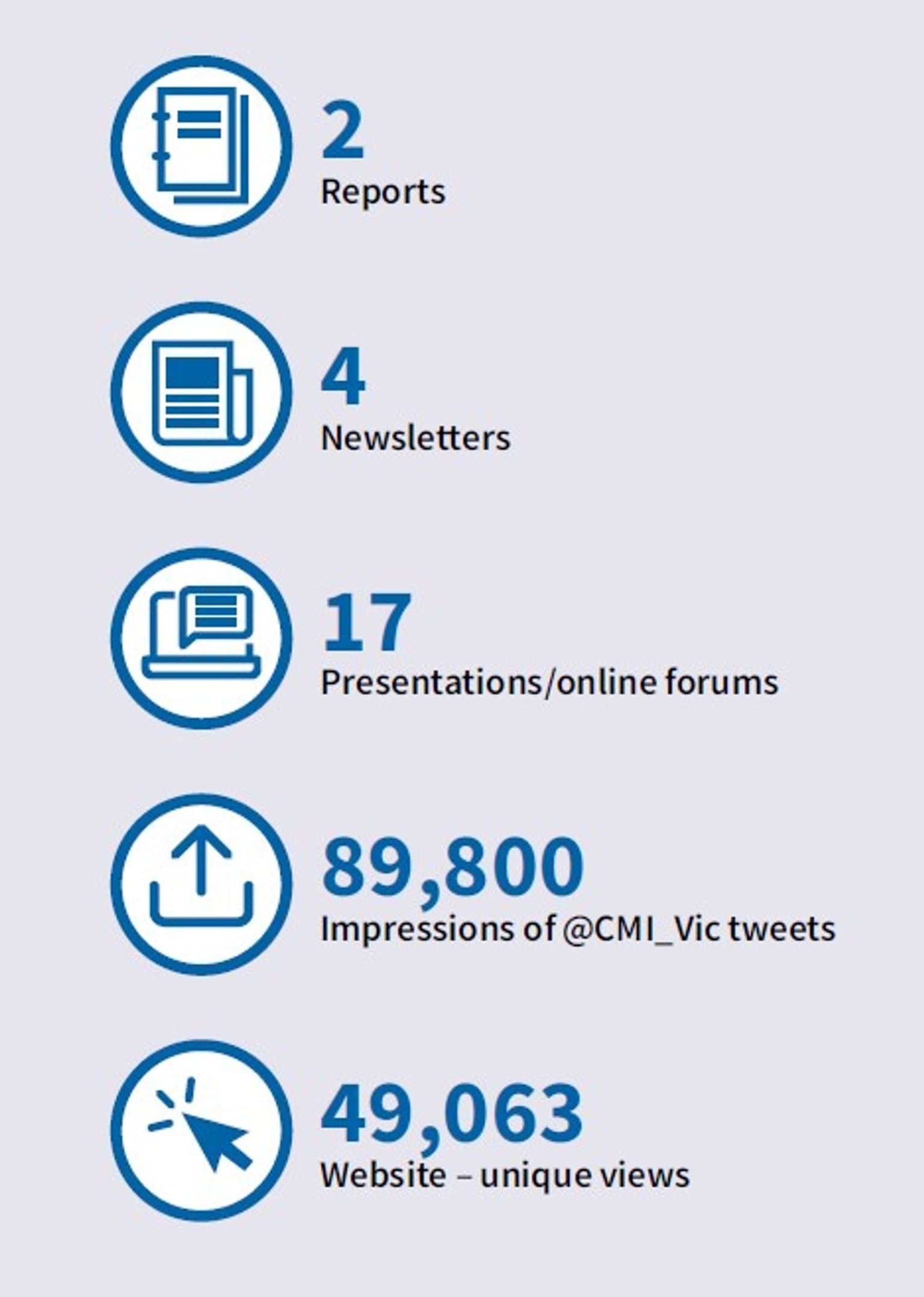

Reports, newsletters, presentations and social media posts are key aspects of the Inspectorate’s guidance and education program. Engagement occurs across various channels to ensure the Inspectorate’s reactive and proactive work is communicated effectively to state government, councils, council representative bodies, the community and other stakeholders.

Newsletter

The Inspectorate published four newsletters to provide information and updates about significant reports, investigations, events and other relevant information.

Newsletters were sent to more than 1,692 subscribers and published on the Inspectorate website. This increased the reach of information beyond traditional mailing lists and assisted in meeting Victorian Government accessibility requirements.

General engagement

We presented to various stakeholder groups and sector representative bodies prior to the October 2020 elections, including joining panel discussions for a Victorian Local Government Association (VLGA) Electoral Integrity forum and an IBAC forum for Public Interest Disclosure Coordinators.

Social media

The Inspectorate continues to use its Twitter and LinkedIn accounts to provide updates on its work and highlight key issues for the sector. We saw a modest increase in queries directed to our @CMI_Vic(opens in a new window) Twitter account about election campaigning practices, councillor or candidate behaviour or council activities. This was replicated in a much greater increase of complaints relating to social media and online activity during the 2020 council elections.

Over that time, we received 351 allegations relating to online content, with 75% of these allegations relating to social media, 10% about email, 11% about websites and 4% unspecified.

On 9 October 2020, we published a guide, with input from the Victorian Electoral Commission, detailing the appropriate method of ensuring social media posts are transparent and their author is clearly stated. (See examples shown on the right.) We also worked with sector representative bodies to deliver messaging to their members on social media usage and will continue to monitor the evolving role of social media in council and election activity and develop suitable materials for our audience.

Website

The Inspectorate website provides easy access to information about the Inspectorate’s work publications, news, media releases and the secure online complaint form(opens in a new window).

| Year | Page views | Top downloads |

|---|---|---|

| 2018-19 | 50,902 | 1,204 - CEO report |

| 2019-20 | 43763 | 1,252 - Yarriambiak report |

| 2020-21 | 49,063 |

1,386 - Campaign donation returns FAQ 1,186 - Election complaint form (hard copy version) |

Source: Google Analytics and Google Data Studio

Corporate information

Corporate information about the Local Government Inspectorate.

Our people

The Inspectorate had 10 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions filled as at 30 June 2021. We also employed 2 contractors for part of this period and had 2 FTE positions vacant.

Challenges and opportunities

As experienced in 2019–20, resource constraints continued to prove challenging in 2020–21, however the Inspectorate has endeavoured to identify and recruit suitable staff and provide training to upskill and retain current staff.

The further proposed reforms to the local government legislative framework will expand the role of the CMI and create new responsibilities particularly in the collation and publication of councillor candidate election donations. The progress and timing of the legislative reform have bearing on the implementation program for the Inspectorate leading up to the 2024 general council election year.

Freedom of Information

The Inspectorate received and responded to one Freedom of Information (FOI) request in 2020–21. FOI requests are handled in accordance with guidelines and processes set down by the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner (OVIC).

Gifts and donations

Our staff were offered and accepted one gift during this financial year. Incoming CMI Michael Stefanovic AM accepted flowers worth approximately $50 from the Australian Local Government Women’s Association Victoria. This gift and all other gifts for each financial year are recorded under a gifts register, available on our website.

Financials

Under the Public Administration Act 2004, the Inspectorate is an administrative office hosted by the Department of Justice and Community Safety and the Inspectorate uses corporate services, including finance, from the department. Financial information is incorporated into the Department of Justice and Community Safety’s 2020–21 Annual Report(opens in a new window).